“Now for a while we shall buy & sell to get gain instead of trying to teach the young.”

Brave words for a young woman with no previous business experience in any era, but they were written in 1859, a time when the doorway to employment opportunities for women was as narrow as it had ever been. So it was with a risky leap of faith that the writer, Mary Page of Hampton, New Hampshire, and her sister Susan, gave up their jobs as school teachers to buy Elizabeth Odlin’s millinery and fancy goods shop in the nearby town of Exeter for $2,300 and reopen it in their own names.

An independent income seemed an imperative for these two as yet unmarried women. Susan was 29 years old and Mary was 26, and by virtue of their ages, their chances of ever finding husbands were rapidly diminishing. Rather than panic at the prospect of becoming bothersome maiden aunts, they chose their path well, the decision to purchase shooting them right to the top of the custom millinery and dressmaking profession. Even in a small town like Exeter, they could now count themselves among the aristocrats of female needleworkers, able to enjoy a certain prestige and command the highest wages.

At the time, thirty-one of Exeter’s 3,309 residents worked in the needletrades, 28 women and 3 men. As tailors and hatters, the men occupied the top tier and were among the well-to-do of Exeter. The tailor Robert Thompson and the hatter Jeremiah Merrill had families and live-in domestics, with assets of $6,000 and $7,500 respectively. Women like Mary and Susan worked as lower-class seamstresses, dressmakers, and milliners; they were mostly single, lived in boarding houses, with assets that averaged $500. They could only dream of making the kind of money their male counterparts enjoyed.

The Page sisters’ younger brother John approved of their venture. “I believe the girls will do well,” he wrote from Illinois to their mother in Hampton. “The millinery business is a very good business because the fashions change so very often. They are stepping into an extensive trade which will be of great service to them. I should advise them to expend a good sum each year in advertising. It will always be a profitable investment for them.”

The Page sisters’ younger brother John approved of their venture. “I believe the girls will do well,” he wrote from Illinois to their mother in Hampton. “The millinery business is a very good business because the fashions change so very often. They are stepping into an extensive trade which will be of great service to them. I should advise them to expend a good sum each year in advertising. It will always be a profitable investment for them.”

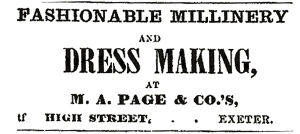

The sisters generally followed John’s advice. Their first advertisement posted in the Exeter News-Letter in April 1860 and ran regularly for the ten years their shop was in operation.

S.L. and M.A. Page in Illinois

“Little transpired that was out of the daily routine of buying and selling and gathering gain, until August 21 [1860], when I diverged from the regular line and landed in the great west,” Mary confided in her diary while on a visit to John, who was teaching school in the Illinois town of Polo (named for the adventurer Marco Polo), some 110 miles west of Chicago.

“Only a few years ago I was a teacher with 50 little children, all looking to me for direction and guidance, and watching my every action by which they would be influenced to either good or evil. Now here I am—and well may this land be called the Great West, for it has produced in me a desire to expand and enlarge my idea of things.”

Acting on that desire, and perhaps to “hunt a husband,” as John in his letters to their mother had hinted was eminently possible in the rapidly growing town, Mary decided to extend her visit into a residency. With Susan managing the Exeter shop, Mary opened a second shop, one that her brother believed would meet with success.

“There is not such a store within a dozen miles of Polo, one of the best business points in the State,” he told their mother, adding, “Mary is doing well for a stranger. I am inclined to think that bye and bye she will have as much as she can do.”

Soon after, Virginia “Jennie” Perkins, another young Hampton woman with a hankering for a little western adventure, joined her as a partner.

M.A. Page and Company

Two years later, Susan announced that she was “a-going to give up her single blessedness” and marry William Cole of Portsmouth, a widower with three small children. As marriage for women generally precluded work outside the home, Mary reluctantly sold her share in the Polo shop to Jennie and returned to Exeter. The partnership firm of S.L. and M.A. Page dissolved and Mary became a sole proprietor under the name M.A. Page.

Without Susan in the shop, Mary struggled to find and keep skilled employees willing to work for what she could pay them. To promising young ladies she traded her knowledge of the millinery and dressmaking trades for their unpaid work. But as often happened, once they were trained the good ones “got the fever” and struck out on their own. With so many new competitors entering the field of female fashion, profits were getting harder to come by.

Mary economized by living above the shop in a frugal flat she christened the “Old Maid’s Hall,” and scrupulously tracked every penny spent. She found working partners willing to invest in her firm, which became known as M.A. Page and Company.

At some point, Mary became the object of attention of one Joshua Getchell, a wealthy but aging dry goods merchant whose nosing around the subject of her living arrangements she found offensive. But her opinion of him changed when his wife died, and, after observing a proper mourning period, they were united in marriage on August 3, 1869, thus ending her career as an independent tradeswoman.

At some point, Mary became the object of attention of one Joshua Getchell, a wealthy but aging dry goods merchant whose nosing around the subject of her living arrangements she found offensive. But her opinion of him changed when his wife died, and, after observing a proper mourning period, they were united in marriage on August 3, 1869, thus ending her career as an independent tradeswoman.

Mary sold her share of the business to her partners and joined her husband, his daughter, and a servant in the Getchell home on High Street, only steps away from the Old Maid’s Hall. While nearly twice her age, acquired in the secondhand-husband market, he was a glorious catch for a woman whose parents fretted that she was too homely to get a man (foreseeing that Mary’s own single blessedness might accompany her to the grave, they had bequeathed her one-half of their Hampton homestead).

The New Mrs. Getchell

For the new Mrs. Getchell, the timing couldn’t have been better. Small, female-owned millinery and dressmaking shops would provide women with employment for years to come, but the future was in ready-made garments, churned out in factories that competed directly with the independent, highly-skilled artisans. And marketers of the new “scientific” methods of garment making sold women on the idea that they could create their own fashionable clothing at home, using their own sewing machines and modest skills. Just one year after her marriage, many of Mary’s former partners and competitors were selling Singer sewing machines as their primary product offering. The victim of post-war industrial expansion, the “very good business” that Mary and Susan had entered a decade earlier was now teetering toward its deathbed.

Originally published in the Hampton Union, April 27, 2017.

A Page Out of History, based on the personal papers of Mary Page Getchell, is available for $10 through the Tuck Museum of Hampton History.

History Matters is a monthly column devoted to the history of Hampton and Hampton Beach, New Hampshire. “Hampton History Matters,” a collection of new and previously published essays, is available at amazon.com and Marelli’s Market. Contact Cheryl at hamptonwriter@gmail.com or lassitergang.com.

Featured image (top): Susan Leavitt Page (left) and Mary Anna Page, c. 1860. Courtesy Hampton Historical Society.

Images (below): Jennie Perkins c. 1860. Courtesy Hampton Historical Society. Her advertisement in the Polo Press, May 16, 1863. Courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society.

Leave a comment